Gordon Fraser’s book, “Song of the Spirit River,” was published in September 2016. The short stories in the book flow along like the Rouge River, meandering through stories of the people who first settled in the region — into the world today. The quiet of the bush and the roar of the river are reflected in Mr. Fraser’s stories, as the people of the community experienced joys and sorrows. Mr. Fraser wanted to share his book with people during this uncertain time, we will be bringing you chapters of his book for free, here on The Review’s website.

Copies of this book are available from The Review. Email: [email protected] to pre-pay for your copy and arrange for safe pick-up at The Review.

And now: here is the fourth chapter of “Song of the Spirit River.”

The CouCou Cache

It was late winter, 1858, when Constant Palache tromped into the yard of the logging shanty, just above La Belle’s falls on the Rouge River. He walked up on snowshoes from Calumet on the edge of a storm; wind moaning through the tall trees and snow falling hard.

He was here to check on production and to plan for the spring break-up which, though weeks away still, was a task his uncle showed him was best planned well in advance. Never leave anything until the last moment, he had been taught, and he followed that lesson well.

So the shanty men were not surprised to see him appear out of heavy falling snow from the river trail as they finished their day’s work. Constant Palache knew all the men in this camp, as he did throughout the far-flung shanties. And all the men knew of Constant Palache, for his reputation as a timber man was legendary. Stories told how he and Big Joe Montferrant had stood back to back against 19 men in a Renfrew tavern; of his time as a Voyageur with Jean Courteau, and more.

Constant Palache greeted each man he met as he made his rounds, snow drifting and darkness setting in. Everyone was finishing up for the day, making certain that the camp would be ready for the morrow and the digging out they knew was coming.

Inside the shanty the winter wind whistled around the chimney; the storm was growing stronger. Men came in out of the swirling snow with stamping of boots and slapping and shaking of coats. The stove in the centre of the room glowed red.

The cook, a crusty old hand and veteran of countless log drives, watched the faces of the shanty men as they entered the big lamp-lit cabin: Charbonneau, the thin wiry one who runs behind the skid team as the logs are snaked out from between the stumps. Bernard, the scaler and sharpener; and O’Riley, self-proclaimed champion with axe or fists. The cook knew their chores for the day were almost finished while his, the task of filling these bellies and keeping the bodies strong, had hardly begun.

More men entered. Plates were set along both sides of the plank table and soon dishes of steaming food beckoned as faces lined with sweat and fatigue turned to eye the feast. But they knew the rule that when the boss was on site, no one took his place until Constant Palache was in and seated.

Talk was small and moments seemed long before the door opened and the bulk of Constant Palache came in out of the dark and the storm. A glance around the room and a nod of his head showed all was in order. Everyone’s task had been completed to his satisfaction and the meal would be served. A hard master but fair he was, and he kept the camps and the men working at their best.

What had been an orderly table was reduced to empty plates as the men ate in near silence. Grunts of appreciation and requests to pass platters were the only sounds until chairs were pushed away and pipes lit. Big pots of scalding hot tea took the place of dirty dishes as men stretched and yawned with the warmth and full stomachs.

The wind outside the shanty rose in a gust causing a whistle in the stove pipe and the cook dropped the pile of tin plates he was carrying to the wash basin. The men who stopped what they were doing to look caught a glimpse of the old man’s face become white, though he turned so not to be seen.

Chancy, called such for the risks he takes while running logs through the spring rapids, was one who remarked on the cook’s face and he called across the room. “Hey Cookie. Why you looking so pale? You see a ghost in the corner?”

Only a small ripple of laughter went up, for everyone knew you don’t ridicule the one who makes the food. The cook was a good-natured soul and he could take a joke, but the comment went unheeded as wind howled through the winter forest.

The cook, forgotten for the moment as he picked up the mess, was not thinking about the teasing. There was something in the storm, and this night, which had him remembering a tale told to him long ago. He had to concentrate hard to do his job; his mind much on the sounds of the winds.

O’Riley, known to be afraid of no man, picked up the tail end of the remark.

“In the future, ghosts will disappear. By the time a new century arrives, no one will believe in haunts. Besides, who in their right mind would fear something you cannot see?”

Charbonneau got up from his chair and went to the stove. He stood there for some time, rubbing his hands together, enjoying the warmth. “Aye, you’re right about times changing, O’Riley lad. But I think we shall always share this world with others we cannot see.” He turned and asked over his shoulder “What say you, Constant Palache?”

Constant sat where he was making entries in a ledger, away from the main table at a desk near one of the cabin’s two windows. The sound of his name being called took him from his thoughts and he looked at the teamster, asking him to repeat.

Charbonneau asked again. “Do you believe in things we cannot see? Foreman, Sir.”

The winds outside the log structure moaned and for a moment the shanty shook slightly under the force of one strong blast. Constant Palache set aside his pencil and stared out the window, waiting for the storm to subside, using the time to think about what he would say.

“Aye my lads, I say like Charbonneau. They are all around us, those we cannot see. Never do I scoff at the spirits. But that was not always my way.”

The cook, still forgotten as he stacked plates and hung cooking pots, was listening closely to the chatter of the men as ghosts and goblins were discussed.

O’Riley told about the wee ones who lived among the stones in the old country of Ireland, expressing disdain for those who believed in such. He laughed as he recounted his grandfather wasting good whiskey on those full-moon nights, when he would set a glass of his best inside the fairy rings.

Delhi, the huge black man whose strength was unmatched by any in the room, recounted how his mother took great caution not to offend the Voodoo doctors at her home in the Bayous far to the south. He spoke of spells and apparitions and dolls.

Around the shanty, man after man told his opinion of denial or belief until all had been heard; except the cook. Outside, the storm grew more intense and as the winter wind howled the men moved closer to the red-glowing stove. The cook remained in his corner though his work was complete.

Constant Palache, who had quit his numbers and ledgers, took a seat with his feet to the stove and lit his pipe. He was about to say something when a tremendous blast of wind blew the door open and for an instant everyone turned to see. By some trick of that awful gale, in that moment a small whirlwind, outlined by the heavy falling snow, circled the opening then entered and dissipated into a heap of white on the floor.

Faster than what might be imagined for an old body, the cook was across the room, slamming the door shut and jamming the bolt in place. All who had been looking at the doorway now found themselves staring at the ghost-white visage of the old man.

“What are you looking at?” The cook snarled. The gnarled face glared back at each of the men. For a moment, the silence in the shanty was complete.

It was as if something had entered the shanty with that snow devil and all were aware of the change. Delhi’s squeeze box fell silent. The checker game between Chancy and O’Riley was forgotten. Bernard stopped whetting the axe he had been working on; he, too, frozen in his place.

The wind moaned sad. A shutter banged and all jumped. Constant Palache was the first to move, getting up to fasten the loose board. He stood there for a time, his attention held by something in the swirling darkness. Before leaving the window he paused to look out one more time, shaking his head slightly as he turned back towards the room and his seat.

The cook remained, back to the door, staring at the gawking faces. “You men who mock the spirits, what do you know? It’s here. Listen. Don’t you hear it calling?” The old man cocked his head to the sounds outside.

Constant Palache sat with his elbows on his knees. Delhi’s blackness was darkened more by the shadows cast by lamplight. O’Riley and Chancy remained face to face over the unfinished checkers game. Bernard held tight to the razor-edged axe.

The storm blew hard, moaning and crying through cracks in the shanty and the shingles overhead. But above these sounds were others, like voices calling over some great distance or time.

“You hear it, don’t you?” The cook’s cragged face was still turned, ear towards the door. “I knew it. When a storm blows like this in these forests the Windigo walks. There, it calls again! It is calling one of its own.”

O’Riley, not to be intimidated by man nor ghost, tossed down the checker in his hand. He rose from his seat, opening his mouth to speak but the cook stopped him with an outstretched hand, palm first. “Listen,” the old man said. “Listen to it speak.”

It did not take imagination to hear voices filled with agony in the winds which howled over the roof and, although the stove was packed full, the room felt cold. The men huddled close to the glowing metal, no one thinking of his cot, preferring company to solitude.

Constant Palache sat with his head in his hands. The cook stared at him. Time seemed thick as molasses before the old man spoke.

“Is it you, Constant Palache? Is it you it has come for?”

Nothing more was said until Delhi jumped, tossing his squeeze box to the floor in his fright, white eyes huge in the dark face. “Something’s out there Boss, something was looking in! There! Again!”

All eyes turned to the window; all except the cook and Constant Palache.

Constant raised himself, rubbing big hands over his rough face, then stood and went to the cook. He took the old man to a chair and sat him down.

The storm now blew so hard that the cabin creaked and groaned under the pressure. Constant spoke. “The Windigo, Cook; you are right. It walks tonight, though perhaps it only comes to remind me of another place and another time.

“Forty years ago this night, my uncle Cyprien Palache disappeared in a storm like this and was never seen again. I remember it like it was yesterday; up at the CouCou Cache.”

The cook, calmer now, stared at the foreman. “Then the story is true, Constant. Tell us what happened.”

Delhi, still wide-eyed from the vision at the window, grew even more so as he listened to the cook. The other men’s attention was on Constant while he walked to the window and looked out. He stood there, seeing the stumps which surrounded the shanty, thinking of how they looked like tombstones as the snow drifted round.

Chancy broke the silence. “Tell us Boss.”

Constant returned to his place by the stove. Delhi was seated again; his squeeze box put away. The storm rattled the roof and all craned their necks to look up.

“Yes, I was there, Cook. Sometimes it seems like a bad dream. Sometimes I wish I could forget.”

Story-telling had to wait while the wild winds toyed with the roof timbers and cried through the shingles. Constant put a match to his pipe and drew deeply.

“Forty years ago. Ah, I was just a young man then. But I was much younger when I first went to work for my uncle Cyprien, to learn the log drives and how to handle timber in the mill ponds.

“Cyprien was a brutal man; very good at getting timber past rapids and running the camps but not a good man. If someone was sick or injured, my uncle gave them no mercy. Anyone who complained was sent home, or beaten to a pulp, for Cyprien was big and good with his fists.

“The nuns in Montreal sold a young lad, Indian Johnny we called him, to Cyprien as a slave; indentured they called it but it was near slavery. Johnny was one half Abenaki and he became an orphan when his parents were drowned. He was placed with the nuns and they sold him. Six years he had to serve, and Cyprien made certain he served full time.

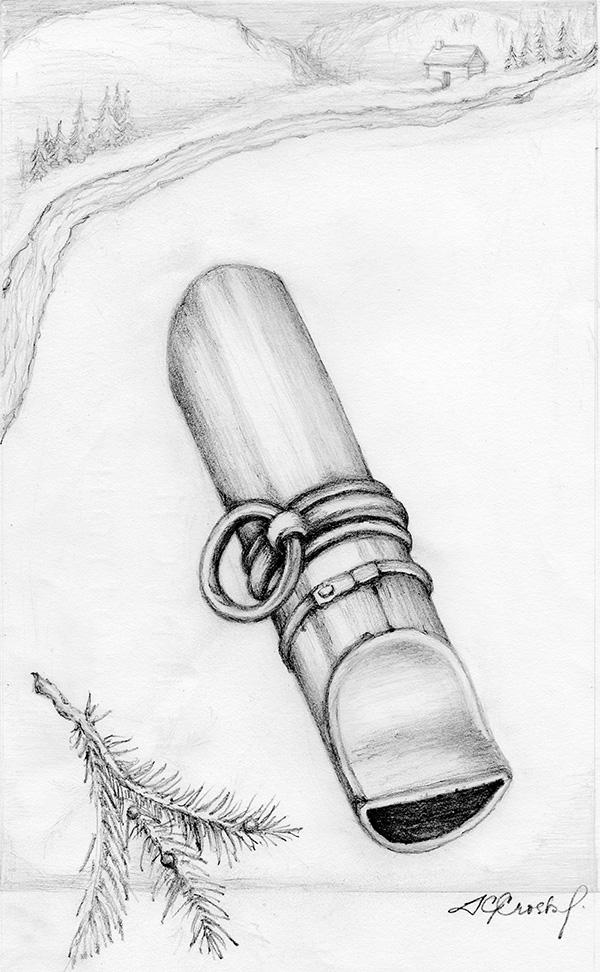

“My uncle carried with him a silver whistle on a chain around his neck and he used it to control the men. He used it to mark the time to start work and when to quit. And he used it to torture Indian Johnny.

“Cyprien would whistle one short blast to mark day start or end. Two calls meant river-right; three was river-left. He did not need to yell to be understood with that whistle, but the men hated it; it sounded evil.

“When Cyprien had a chore for Johnny he would blow that whistle one long note, and god help Johnny if he did not respond at once. And Cyprien always had chores for the young lad. Any time of the day or night, my uncle would call Johnny with that whistle and Johnny would come running only to be slapped or made to go without a meal for reward.

“Sometimes the men would ask Johnny why he did not just slip away, get to another crew. But he would not. He was proud of his heritage and even though an orphan he would do nothing to disgrace the dignity of his forefathers. He would bear the beatings and work out his indenture.

“Indian Johnny and I became friends, for we were not far off in age. Sometimes when we talked, he told me of the spirits he worshipped, the way his father had taught him. He had to be very careful that Cyprien never saw him, but when Johnny had a little time to himself he prayed to the Windigo.

“He said the Windigo is the spirit of the storm; the spirit of the deep forests. He told me that the Windigo could protect those who were proud and brave, and would destroy any others in its path when it walked.

“But I did not really follow all what he said. Except that I did see that Indian Johnny was true to his indenture and brave in facing my uncle Cyprien.

“Then in the winter of ’18 my uncle took me and Indian Johnny with him on a trip far up the St. Maurice River, way north in Quebec. At La Tuque he hired Jean Courteau as his guide and we headed out into the forest.

“All the way on that trip he used the whistle. There was no stopping until it blew, and he used it before the light was in the sky to get us to break camp. He made Indian Johnny carry a double pack and if he got more than a few steps behind, Cyprien blew that cursed whistle to make him hurry more.

“We travelled for two days straight; through the snow, across frozen lakes and steep hills on the east side of the St. Maurice. Beautiful country, and wild. Would have been a pleasant place; except for Cyprien.

“The third day on the trail, clouds closed in and the wind began to blow. By mid-afternoon the snow came thick and heavy, and it was not a night to spend in a lean-to; if there was a choice.

“Jean Courteau knew of a shelter a few miles farther on along the shore of a river. A place where the tribes sometimes met traders to exchange fur for steel, so there we headed.

“The darkness came early that afternoon and we pushed hard to keep ahead of the storm. Indian Johnny suffered badly, trying to keep up to Cyprien, Jean, and me, for he was carrying double weight and not yet even 17 years old.”

Constant Palache paused in his recount while he re-lit his pipe. The storm outside was almost a continual cacophony, but everyone’s attention was on the story.

“Keep going, Boss.” Charbonneau said. “So what happened?”

Constant took a deep draw of his pipe and settled into his chair.

“Well we arrived at that camp, the CouCou Cache, Jean called it; on a bend in the river, just as night set in. It was not more than a rough log shack with dirt and sod for a roof, but it was solid and tight and had a fireplace.

“The storm blew like it does this night, maybe harder, and we could see no farther than our own feet. Cyprien made Indian Johnny search for wood to burn even though the lad was almost dead of fatigue. He did it though and we got that Cache warm.

“All might have gone well for we had food and shelter and Jean said we were no more than a one-day walk from Les Rapides Blanc – the destination we were headed for. Yet the way that storm blew we wondered if the old shack could stay standing. So we huddled around the fireplace and waited.

“As the place warmed up and uncle Cyprien loosened his jacket, all hell broke loose. He had lost his silver whistle. He searched through his overcoat and even his underwear, but no whistle.

“Cyprien went mad. He half tore the shack apart, and got young Johnny to empty all the packs on the floor, but still no whistle. My uncle paced the floor and would hear nothing about getting some food ready. Only that whistle mattered and he must find it.

“Jean and me, we tried to tell him he could get another as soon as we got to Quebec or Montreal, but he would hear nothing. That whistle was special; could not be re-made, and no other would do. That’s when he started to blame Indian Johnny.

“The storm blew hard that night also lads, terrible hard, but when no sign of the whistle was found, Cyprien said it was all Johnny’s fault the whistle had gone missing. Jean asked how that could be, since Johnny never touched le maudit sifflet. That made my uncle Cyprien real mad.

“Cyprien stood six-foot-six in his sock feet. When in a rage in a small room, it was something to behold. Like a crazed bull in a pen, he was, but still he had sense enough not to tackle Jean Courteau, and I was kin; so he cursed Indian Johnny.

“Nothing would do but Johnny must find that whistle, even if it was in the snow somewhere on our back trail. But lads, the night outside was not a place to be. Step outdoors and a man might never find the Cache again in the dark and drifts. Never mind that though. Indian Johnny must find the whistle and it had to be somewhere between here and our last camp.

“So Indian Johnny bundled up and headed out. Jean and me, we were feeling real bad for young Johnny. But my uncle said. “What good is being an Indian if he cannot track,” and we watched him head out of the door.

“After he left, the storm got stronger and stronger until it seemed the roof would fly away. My uncle Cyprien just sat by the fire and stared and did not say another word. Me and Jean, we were hoping the best for Johnny out on such a night.

“But time went by and Johnny did not return. The storm was making noises like it does tonight; almost like voices. Then it all went silent; like a tomb is silent. Not a sound. No wind, no voices, you could have heard a mouse walk if there were any.

“Cyprien, he went even madder in the silence. He stared around as if lost. It was then we heard the Windigo. Outside, from somewhere above the cabin, there came sobs as if a man in terrible sorrow. Then moaning and whimpers like someone in mortal pain, then shrieks of wild laughter.

“Then we heard the whistle! Louder than my uncle ever blew, it called in one long tone: the same tone Cyprien used to call Indian Johnny.

“Well my uncle Cyprien, when he heard that call, he jumped up so quick that me and Jean had to get out of his way. Then he just ran to the door and out into the storm. Nobody ever saw him again.”

Constant Palache pushed back his chair and looked at his now-dead pipe, deciding not to re-light.

The cook broke the silence. “What happened to you and Jean, and Indian Johnny?”

Outside the storm was abating, the snow still falling heavy. Constant stretched and re-settled in his chair.

“When morning came, me and Jean found snowshoe tracks big as a double-bulk sleigh all round that CouCou Cache. Search as we might we saw no trace of Cyprien or even which direction he went. So we headed back to La Tuque and Quebec town.”

It was O’Riley who asked. “And Indian Johnny, Constant? What became of him? Did he survive?”

“Johnny sent word that he is doing well. When he left the CouCou Cache he headed straight to Lac St. Jean where some of his kin live. He stays there now, and traps and hunts the moose.”

The woodstove was stuffed full again, and quietly the men made their ways to the cots. Outside the snow stopped falling and the wind died away. One by one, stars filled the spaces left in the sky by departing clouds.

Long before dawn, the cook had the table piled high with pan bread, molasses and bacon fat. The aroma of coffee filled the air.

Charbonneau, the teamster, was the first to open the door; anxious to check on his horses. But he had only pushed his way a short distance through the drifted snow when he called. “Hey Boss, you men, come see!”

From where he stood, a trail of footprints was plain in the fresh-fallen snow. Deep and wide they were, heading right off into the forest. And there, hanging on a peg by the cabin door, was an antique silver whistle.

Constant Palache pocketed the whistle and later that day, as he was leaving for a shanty over in Avoca, he took the time to stand on the edge of La Belle’s Falls. With the late winter sun shining bright, and where the open river drops over sheer rock, he stood and thought of his uncle Cyprien and Indian Johnny and the CouCou Cache.

Then he tossed the whistle into the water and went on his way.

The CouCou Cache was situated on the Windigo River, a short distance from where that river ran into the St. Maurice in the district of La Mauricie, Quebec. Who built it or when is lost to history. It was used as a Hudson’s Bay trading post from 1875 to 1913; though it is known to have existed long before that.

In 1938 an electrical power dam was constructed on the St. Maurice River and the site of the old CouCou Cache is now beneath the waters of Le Reservoir Blanc.