Living with renal failure was like being killed slowly, says Naomi Mahon. Although the Vankleek Hill woman’s kidney function had been declining over a 15-year period, things reached a breaking point when doctors told her last year that with only 11 per cent kidney function, it was time for her to to find a kidney donor.

“I didn’t want to do that,” said Mahon. Although she had strong connections to family and to her church community, the last thing she wanted to do was ask people to donate a kidney. All along, she had kept her condition to herself.

It turned out that none of her three daughters was a match for Mahon’s blood type. So they were out. But one of her daughters began the process of preparing to donate a kidney as part of the kidney paired donor program, which meant that Mahon’s name would have been on a list for a kidney. But finding a match could have taken years. (Kidney paired donation is a program that matches transplant candidates with suitable living donors. It gives people the chance to become a living kidney donor while ensuring that someone they want to help receives a needed kidney, even if they are not a direct match.)

“I did start to tell people in our congregation,” Mahon recalls, referring to St. John’s Anglican Church in Vankleek Hill. And Mahon says that from the start, she had decided she would not turn to dialysis despite her failing kidneys.

Mahon knew more than the average person as she faced renal failure. A retired nurse, she had spent several years working at the Ottawa Hospital Riverside Campus where she cared for patients on 7 Northwest, in the nephrology unit.

Fast forward to May 4, 2023. Mahon found herself in the same section of the hospital where she had worked for years–but this time, she was the one waking up with a new kidney. Well–new to her. When St. John’s parishioner Randal Storey learned she was looking for a kidney, he had immediately said he would get tested to see if he was a match. He was. The day he had volunteered to get tested, Mahon remembers going home in a state of disbelief. Her husband was overwhelmed when she told him about the offer.

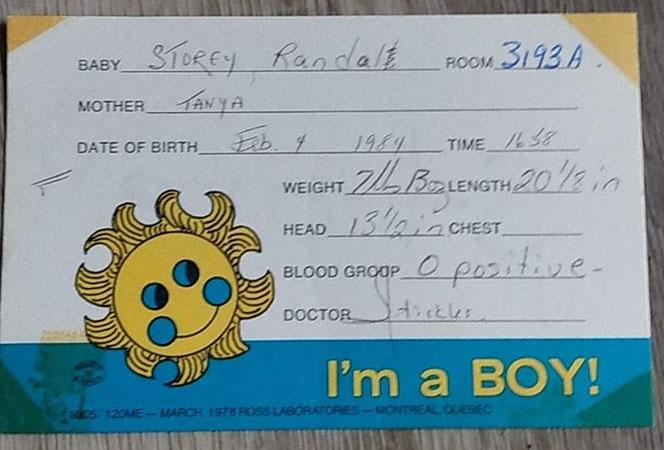

“We had been decorating the church for Thanksgiving in 2022 with the altar guild and that was when I heard that Naomi was looking for a kidney donor,” Storey says. “We were talking in the parking lot afterwards. I learned that her three daughters could not donate to her,” Storey continued. He offered to get tested. “Naomi asked me what my blood type was. I called my mom right on the spot, and she texted me a picture of the bassinet tag from when I was born. I was O positive, just like Naomi.”

Storey says that he began the procedures required to become a kidney donor. The process includes ensuring that the donor is absolutely certain about donating a kidney.

“I was advised to take a full month to think about it,” Storey said. The donor’s mental health is also important and that is understandable, he says. In the end, he met with a psychiatrist who agreed that Storey was in a good place to proceed, despite him having his own mental health challenges in the past.

Mahon learned in early April that all systems were go for the kidney transplant. She and Storey were booked for surgery on May 4.

Mahon was not worried. She knew she would receive good care after the transplant and says the process was better than she had expected. “Five or six of the nurses who cared for her on 7 Northwest in the nephrology unit were former colleagues. “Maybe I got special treatment,” she joked.

Waking up after surgery, a dark cloud had lifted

“When I woke up at 4:30 a.m., I felt like a dark cloud had lifted. I felt different right away,” she says. “In the years before the surgery, I had lost my spark for life and had no energy,” Mahon said. The transplant gave her life, she says simply. “It really was a miracle. It makes you wonder where this all came from,” says Mahon, who feels that a higher power had to be involved.

Storey also feels that there were other forces at work. “We keep using the word serendipity, but there is more to it than that. I did this because I felt I was put in that church for a reason. It felt like the Creator was putting us together.”

Storey is new to the area and to St. John’s Anglican Church. He moved to the Alfred area with his partner in 2020, a direct result of the COVID-19 pandemic and the urge to get out of the city and live a different life. He met Mahon first virtually as he connected with the Anglican parish and knew her as the church treasurer. Eventually, he connected with several Anglican congregations in the area, but he says after attending church and church events in person, the Vankleek Hill church felt like home for him.

Storey is a bubbly, enthusiastic volunteer and gives a lot of his time to the congregation. Just last year, he was the impetus behind a new event which took place on the church hill. Called “Art in the Garden,” the event included almost three dozen vendors under tents which flanked the sides of the driveway going up the church hill. Hundreds of visitors attended the first-ever event. (This year’s edition takes place on Saturday, August 12, 2023.)

What he gives to his church and to the community fills him up, he says. There is an energy that unfolds within when you give, he says. “It’s like a warm blanket.”

That warm blanket of the church community enveloped him and Mahon during the transplant procedure and in the days of recovery that followed. He said there was a prayer chain and that there were people across the country thinking about him and about Mahon.

“The thank-you messages and the prayers that have come our way in the past few weeks are incredible,” Storey said.

“These are my Ontario moms and grandmothers,” Storey said, referring to the congregation with a smile. As if on cue, two long-time members of the St. John’s congregation were in The Review reception area and when they learned Storey was being interviewed, they came in to give him a hug and ask him how he was doing. It was only May 11, seven days after his surgery, but he had been out and about on Main Street and had stopped in at The Review to speak with this writer.

After they left, Storey smiled and said, “There you go. See what I mean?”

One thing he wanted to emphasize was that getting tested to see if you are a match is not a commitment to proceed. You are protected, he said, in case you are a match but have misgivings. The donor team and the recipient team work separately and confidentially on behalf of their patients, according to both Storey and Mahon.

“Sign your donor card,” says Mahon. Donating an organ to someone is the greatest gift you can give, she commented.

“Randal is the son we never had,” says Mahon. She has spoken with Storey’s mother by telephone. “Randal’s mother says he was always thinking of others. Even at five years old, he sorted through his Christmas gifts and told his mother that he only wanted to keep a few things and that they should give the rest of the gifts away.”

While Storey is out and about as usual, Mahon is keeping a low profile as she recovers, wearing a mask if she does go out in public and doing her best to protect her immune system. She has a lot of restrictions just now, she points out as she is on a cocktail of drugs to prevent her body from rejecting the new kidney.

“I cannot thank everyone enough for the prayers and the many messages received before and after my surgery.”